I read once that grief can work like a yo-yo. It spins away, then bounces back, slapping your hand on the return. That seems an apt description for my mourning of things lost over this year-plus of pandemic.

A few days ago, I took my four-year-old to City Park on her bike. She glided along happily, delighted to discover the rainbow path that leads to a small cache of golden minerals by the Museum of Science. Watching her should have been a happy moment, but instead I felt a lump in my throat. I realized that she did not remember the rainbow path or the museum or coming here at all. More than a year had passed since we last visited the Museum of Science, and the memories of four-year-olds are short.

Pre-pandemic, we visited the museum regularly. I vividly remember taking my son to a presentation on galaxies when he was about my daughter’s age. He sat, eyes shining, through the museum educator’s talk. Then, my usually shy kid raised his hand eagerly and asked, “But where is the Death Star?”

This may not have been a brilliant moment for science education, but it certainly has become a favorite story of my son’s. I felt the lump in my throat grow as I reflected that, by the time we finally take my daughter to the Museum of Science, she may have moved beyond questions like that.

These moments of mourning keep ambushing me these days. Our gradual progress to a post-pandemic world elicits them, as I return to people and places I have not seen, in many cases, since 2019. I imagine I am not alone in this. Even for those who have not suffered serious loss, such as the loss of a loved one or physical damage due to COVID infection, we all have missed visits with friends and family, birthday parties, music concerts, and so on. We all will undertake a grieving process in varying degrees. As parents, we must remember that children should undergo the same process, and they need our help.

For at least two reasons, children will struggle more to come to terms with their emotions about this strange year. First, children cannot simply replace missed experiences to the extent that adults can. Kids turn into different people every few months, and the way a child experiences an event at the age of four differs drastically from her experience of the same event at five. When my daughter was three, she was too scared of Santa to sit in his lap. This year, she lobbied hard to see him. “Santa does not get COVID,” she told us firmly when we demurred. Next year, I suspect she may buy into my older daughter’s world-weary cynicism: “that’s not the real Santa.”

Second, children generally lack an adult’s ability to identify and understand their emotions. A child may know she feels awful, but not that the cause is loneliness or anger. If she cannot identify the emotion, she cannot acknowledge it or put it into perspective. Perhaps more often, the child does not even stop to notice her feelings; she simply lashes out. In our house at least, frustration over social distancing has resulted in frequent sibling bickering and more than a few temper tantrums.

How then do we help our kids come to terms with all their losses and move on from this year? As adults, we know that we should acknowledge our feelings and let the mourning process play out. This is not an easy path of course, but at least we have a path to follow. For kids who do not know what they were feeling in the first place, this route seems out of reach.

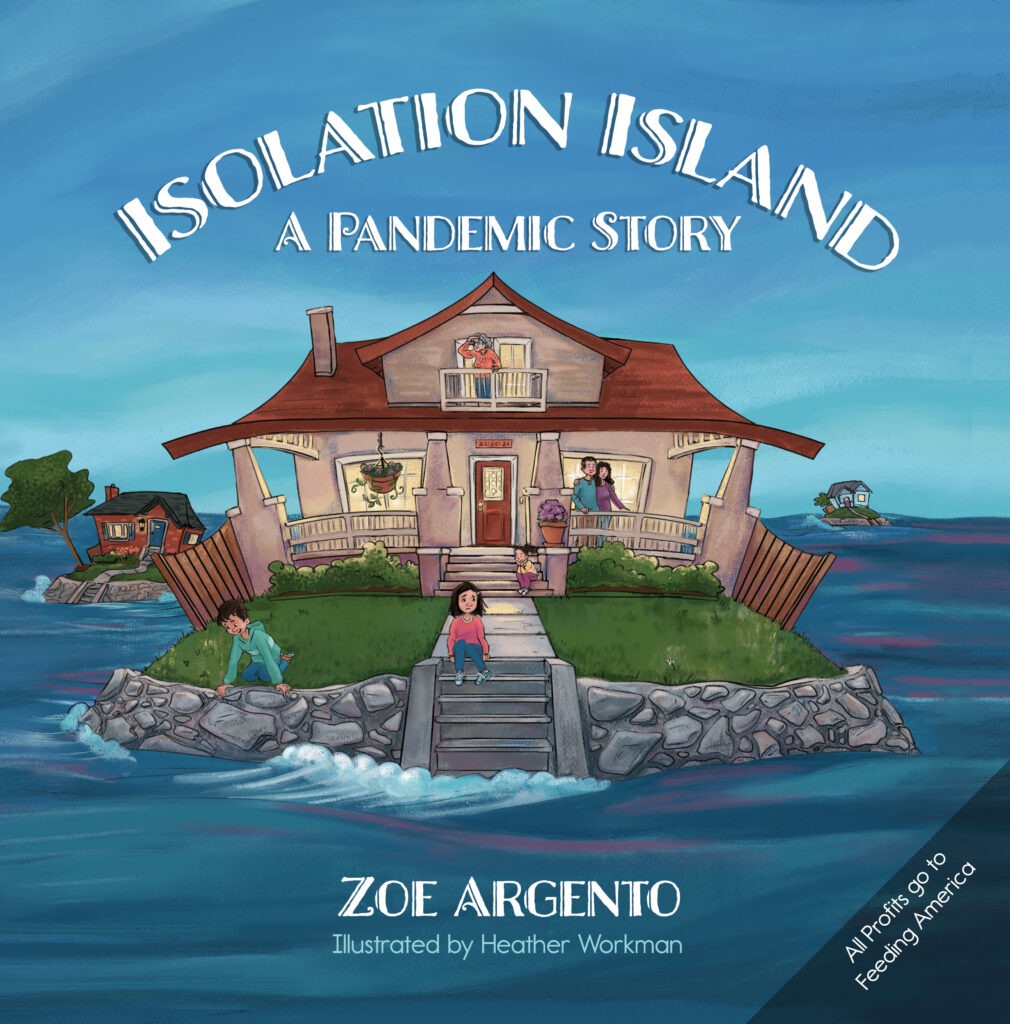

Early in the pandemic, I found that stories soothed my anxious, frustrated kids, especially stories loosely about the pandemic. I told a story about people stuck in bubbles who couldn’t escape. There was a tale about waking up one day to find that Denver had disappeared. Our house sat alone on the plains with nothing but grass between us and the horizon. My kids especially liked the story in which the houses on our street broke into islands separated by the sea. The kids had to holler at their friends across the water. The idea of being so close yet so far really resonated with them.

Stories seem to help my children work through emotions in a way that felt safer. It’s only once upon a time; the ocean clearly has not flooded our street. But imagining houses floating away appeared to assist my kids with processing the scenario in which we felt marooned on our own islands. In the hope that these stories might help other children, I published a children’s book about the pandemic. My goal was to tell the experience of the pandemic from the perspective of a child. The book’s illustrations particularly bring that experience to life, showing kids waving to each other from houses that have turned into islands and floating around in bubbles. The profits go to Feeding America, a hunger relief organization.

Although the pandemic appears, finally, to be coming to an end, the emotional experience may not yet be done with us. To truly move on, we likely need to keep telling the pandemic story to ourselves and to our children. Someday, perhaps our children will tell their children about the year of islands and bubbles and masks and, most importantly, how they survived and life continued. Sometimes, the hardest times make the best stories.

Featured Image by Xenia Photography